First published: Spring 2022

Discredited by the state for anti-Soviet activity, a group of dissenting artists in the 1960s channelled their creative energy into the growth of Russian naïve art

In the decade following Stalin’s death in March 1953, a gradual cultural relaxation occurred in Russia, a brief period of artistic freedom. Of course, this in no way resembled the freedom available to Western artists who were at liberty to explore the personal and political within the psyche of the post-war period. Nonetheless, there seemed to be a softening of the autocratic structures that constrained Russian society, a culture where individual thought and expression had been comprehensively and ruthlessly suppressed.

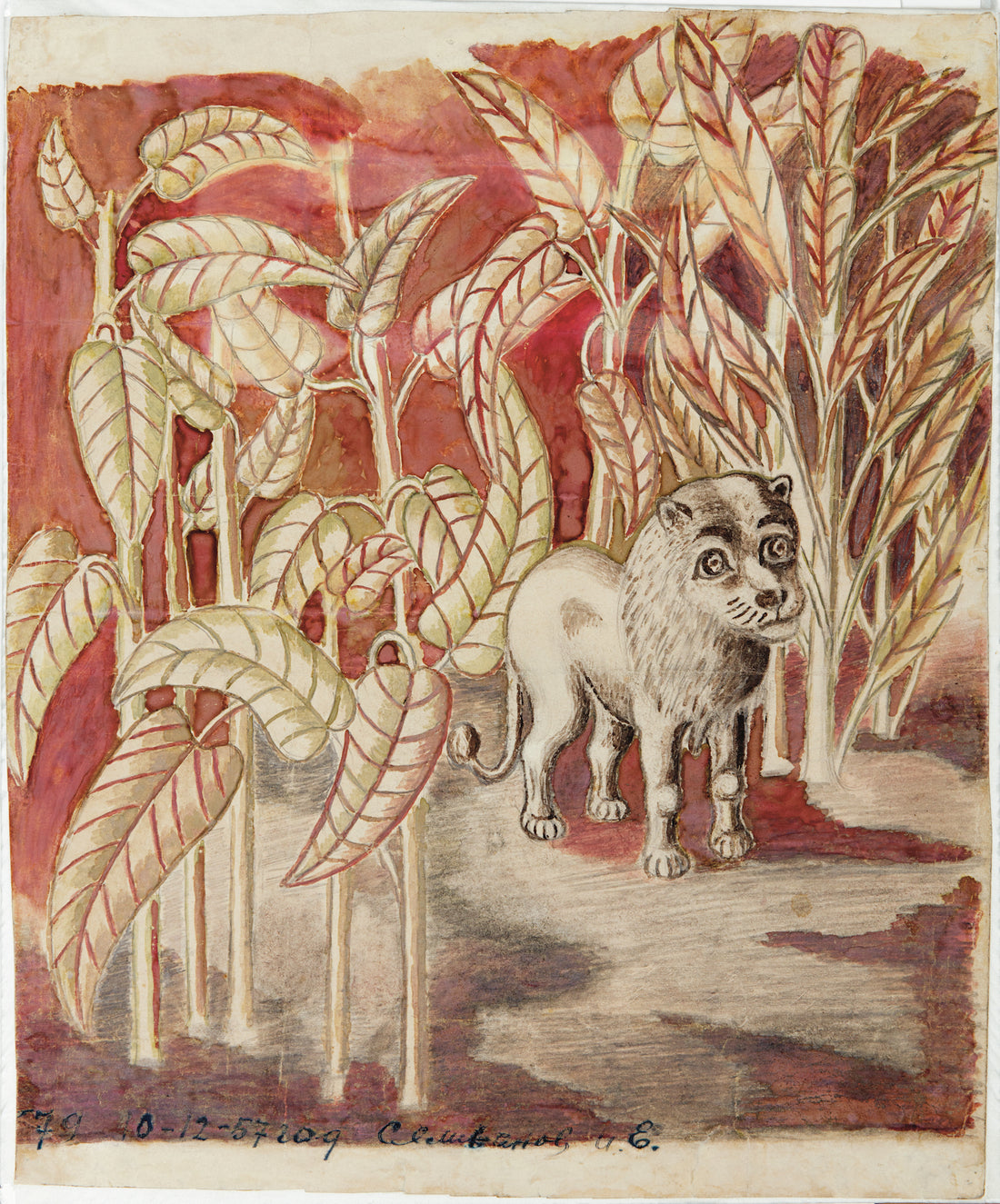

Ivan Egorovich Selivanov, Lion, 1957, watercolour, pencil and whitewash on paper, 13 x 16 in. / 34 x 41 cm, courtesy: Moscow Museum of Modern Art

Ivan Egorovich Selivanov, Lion, 1957, watercolour, pencil and whitewash on paper, 13 x 16 in. / 34 x 41 cm, courtesy: Moscow Museum of Modern Art

After the 1917 revolution, there was an intense push to create a new art for a new ideal society. The Socialist idea that personal leisure was an opportunity for people’s creativity was explored. It was the period of the avant garde, and this experimentalism extended to self-taught artists. Among the artistic intelligentsia there was great enthusiasm for the vivid and non-Westernised traditions of peasant culture. Many, like Wassily Kandinsky and Kazimir Malevich, believed the new proletarian art should be built on its foundations.

Pavel Petrovich Leonov, At the Factory, 1970s, oil on cardboard, 28 x 40.5 in. / 72 x 103 cm, courtesy: Moscow Museum of Modern Art

Pavel Petrovich Leonov, At the Factory, 1970s, oil on cardboard, 28 x 40.5 in. / 72 x 103 cm, courtesy: Moscow Museum of Modern Art

In the 1920s and 1930s, the idea of art education by correspondence emerged. Russia is vast and there were not enough artists to produce propaganda art for the decoration of public spaces. At the Russian State House of Folk Art, correspondence courses in painting and graphics were devised. At first, no-one thought painting could be taught by correspondence but the initiative was a success. All sorts of people – workers, housewives, prisoners, from all over the country – received training.

Vasily Tikhonovich Romanenkov, The Birth of the World, 2004, pencil and felt-tip pen on cardboard, 18 x 30 in. / 46 x 76 cm, courtesy: Collection Bogemskaia – Turchin

However, by 1934 – when the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks adopted a resolution ‘On the restructuring of literary and artistic organisations’ – Socialist Realism became the only permissible ideological approach. Amateur artists were expected to conform to the subject matter and technique of professional artists who obeyed strict codes laid down by committee. Amateurism was not a means of self-expression as might be understood in the West, but part of an apparatus to create a new kind of human being, one whose consciousness had been ignited by communist ideals. Amateur art was strictly supervised. Titles of works by correspondence course graduates might include: A Working Group is Studying the Stalin Constitution; Young Lenin Listens to his Mother’s Piano; Comrade Stalin among Collective Farmers.

After Stalin’s death, his successor Nikita Khruschev famously denounced the personality cult surrounding the dictator. Fissures seemed to be appearing in the cultural deep freeze. The “Thaw” had begun. By 1960, the correspondence courses for amateurs had become part of a new independent organisation: The People’s Free University of the Arts by Correspondence (ZNUI).

by JAMES YOUNG and TATYANA SINELNIKOVA

This is an article extract; read the full article in Raw Vision #110