First published: Fall 2018

China has the largest older population in the world – by 2017, there were more than 150 million people aged 65 and over. The everyday life of this enormous-but-largely-silent community is shockingly homogeneous. The majority of senior citizens in China continue their roles as family caregivers, helping their children with household chores and looking after their grandchildren. Their free time is usually spent on fitness-related activities as they try to battle old age, ailments and feelings of emptiness by sticking to healthy routines and diets, travelling, being physically active, and spending time on some kind of hobby. For 71-year-old Shao Bingfeng, however, life after retirement has meant much more. She became an artist ten years ago, and today her work is on show in galleries in Paris and Beijing.

A petite woman with grizzled hair, Shao is full of energy and looks younger than her age. She lives with her daughter’s family in the suburban town of Yanjiao. After minor surgery last year, she decided to settle in the area for easy access to the hospital. The town is about 20 miles from Beijing and the low house prices have turned it into a satellite city that has attracted a lot of artists who work in Beijing. During the day, the residential area is very quiet. Shao’s daughter’s apartment is on the ground floor and has a small backyard filled with plants.

Shao’s room faces the yard, and her bedside work table is covered with art supplies – a convenient setup for her to continue painting after her siesta. When she is working, Shao stands with unwavering concentration, sometimes all afternoon. Her daughter wishes she would not work so hard, but Shao thinks there’s no better way to relax than painting.

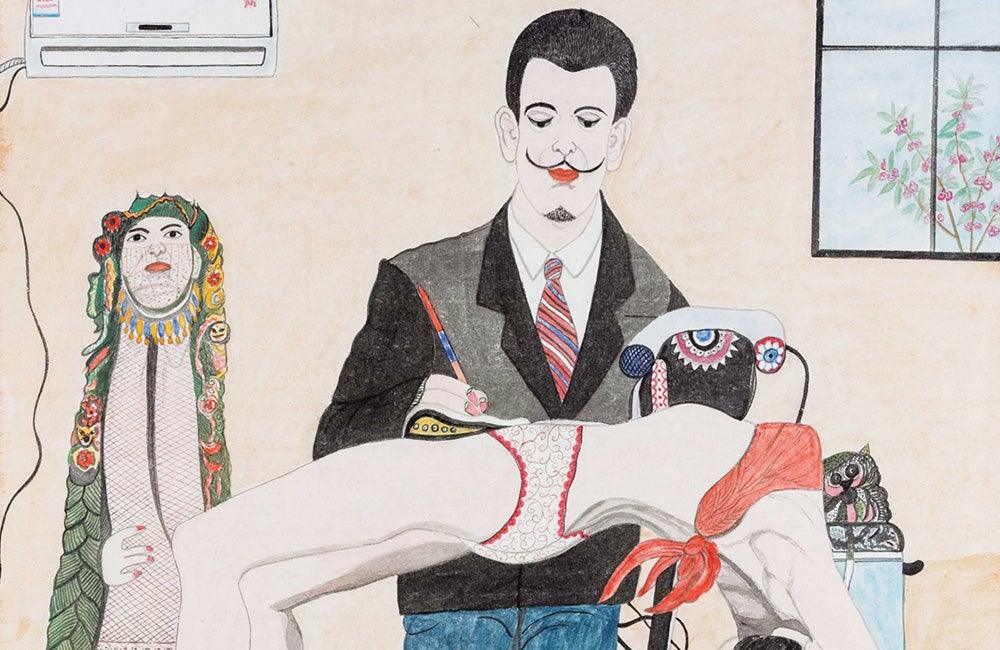

Writing in a Difficult Way, 2018, 27.2 x 27.2 in. / 69 x 69 cm. All works are Chinese ink on rice paper

An iPad on Shao’s work table stands out among the palettes and brushes, with an image on its screen: a girl in black (who appears to be Eastern European) lies on her side on top of a low cabinet. A leopard inside the open cabinet seems to be fascinated by the girl’s hanging braid. Shao’s painting of this image retains the same basic composition, but the Eastern European girl has been replaced by a Chinese country lass in a floral print dudou (traditional Chinese bodice), the pillow and the cabinet have been decorated with finely crafted traditional patterns, and a few more leopards with surprised expressions have joined the lone one in the original picture. Shao uses traditional Chinese pigments and thin ink brushes for colouring, which produces an unassuming tone that nonetheless serves to create tension and depict all kinds of eerie scenes. Those who see Shao at work for the first time would probably be intrigued by her method, but she has been working this way for more than a decade: she is not really duplicating, because her creations are completely different from the references she uses. A painting takes Shao a week to a month to finish, and sometimes she recolours old works long after they are completed if she spots something unsatisfying. Over 500 completed rice-paper works have already come out of Shao’s daily exercise, all with a distinct, unified style that belongs to her and her alone.

Shao’s reference pictures are sourced from the internet by her daughter, then Shao picks what she finds “interesting” to paint. Judging by her recent series’ (such as the “Circus”, “Dalí” and “Hairdressers from the Industrial Period” series), her definition of “interesting” must contain elements such as exaggerated dramatic intensity, rich content and novelty scenarios. She has even tried her hand at medieval altarpieces. The colour and resolution of the original image is irrelevant to Shao.

Creating lifelike images is never Shao’s goal; her brushstrokes are characterised by their unconstrained intuition and heartfelt sincerity. The Western figures in her early paintings all have East Asian features, and she finds painting children especially challenging. She admits that it’s a pity she can’t paint them better than “dwarves with adult heads”. From clothing to furniture, wherever decoration is concerned Shao is drawn to traditional Chinese patterns. Winding curves, floral patterns, auspicious characters – these images are normally used to represent good fortune and happiness in Chinese folk art, but in Shao’s work they are found on the bikinis and surfing boards of modish girls. Even the clown who plays Rigoletto in the circus looks like a Peking Opera performer with a pair of embroidered shoes. Shao likes to fill the background of her paintings with everyday objects: the wall behind Dalí is decorated with a wall-mounted air conditioner with exposed ducts and a column heater, both commonly seen in Chinese households; a traditional porcelain flower vase sits at the feet of Madonna, and potted plants from Shao’s own backyard can be found in most of her paintings.

Translation: Wei Ran

This is an article extract; read the full article in Raw Vision #99