First published: Spring 2018

The circus, money, space exploration, everyday Soviet life, word games and America. These are some of the themes woven into the fabric of Gennadiy Lukomnikov’s (1939–1977) creative output. Leaving behind hundreds of works, this overlooked artist and writer, who worked in total creative and intellectual isolation, remains practically unknown. Born to a middle-class, Jewish family in Baku, the Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia in his youth. Living with his mother and receiving a modest pension for his mental illness, he spent his life in and out of mental institutions. But continually processing daily life through the prism of a rich, witty and diverse imagination, he found an output for his world view on paper.

Lukomnikov held a string of jobs (tree planter, assistant cartographer, draftsman, photographer, geological digger), but was unable to keep any for too long and was often fired. In 1961, he had an early job as a caretaker in the Government House of Baku. He had been placed in the role by his father, who worked as an assistant to the Minister of Agriculture, and he fell in love with an Armenian girl who operated the lift. They married, and in 1962 had a son, German (named after the cosmonaut, German Titov), but she divorced him not long after, when she came to understand the extent of his mental illness.

Lukomnikov’s father died a few years later and he spent most of his adult life under the guardianship of his mother. It is through his son – a celebrated poet in Russia – that Lukomnikov’s archive remains intact. But even German only began to appreciate this legacy as the artistic manifestation of a complex and intricate worldview a decade after his father’s death. Lukomnikov left stacks of ragged paper filled with modestly-executed sketches in biro and pencil, home-made books, wooden cut-outs, photographs and exercise books of poetic verse. Lukomnikov died aged just 38, from a mysterious and tragic incident in 1977 involving either a fall or a jump from their flat’s balcony.

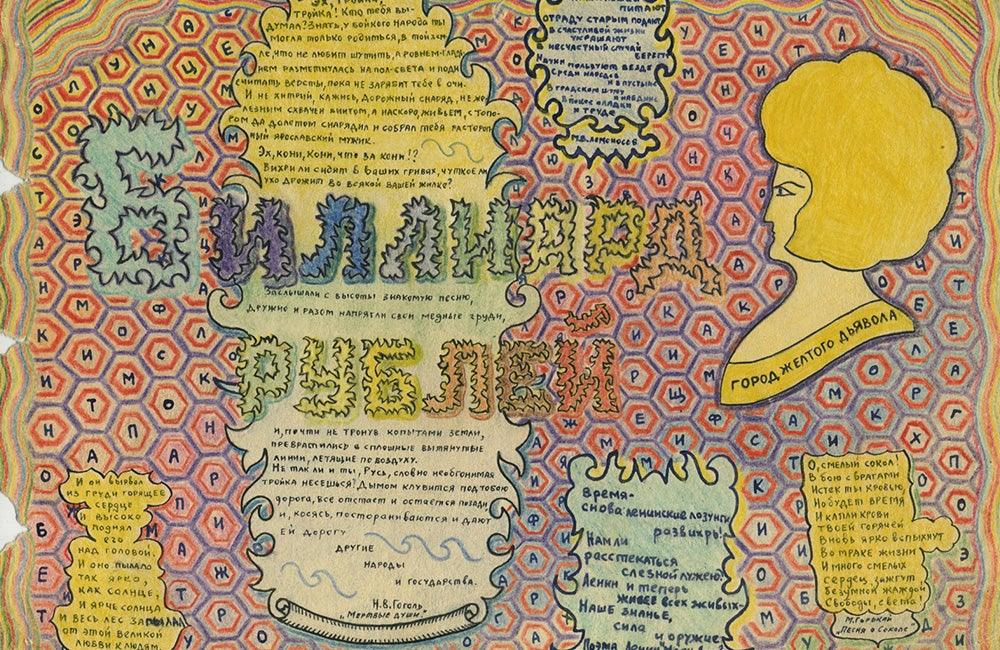

Untitled, Lukomnikov, 30 x 20 cm

The longest lasting job that Lukomnikov managed to hold down towards the end of his life was at the Baku Opera and Ballet theatre, as a stagehand and then a set painter-decorator. He was engrossed by the theatre, which can be seen in a series of works it inspired, revealing a leaning towards performativity and grandeur.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the modesty of his lifestyle, there is an opulence in Lukomnikov’s works. Money is a recurring subject, seen in a series of intricately-drawn banknotes in denominations that vary from three roubles to one million or one quadrillion. There are also notes for “one million smiles”, or “one hundred thousand Whys” (a paraphrasing of Rudyard Kipling). Some notes have no monetary denomination. Emblazoned with the profile of a stern, large-haired woman in place of Lenin’s portrait, they are decorated with intricate patterns and interwoven text: Soviet slogans, poetry, quotes, aphorisms and word games.

This is an article extract; read the full article in Raw Vision #97