First published: Spring 2020

Barber, preacher, husband, artist – Elijah Pierce led a full life built on faith, love and a prodigious talent for woodcarving

When Elijah Pierce was “discovered” by the art world in the 1970s, he was already well known as a woodcarver, preacher and barber in his African-American community in Columbus, Ohio. He had a barbershop only three blocks away from the Columbus Museum of Art (the Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, at the time). He cut hair in the main part of the shop, and in the back was a room in which he worked on his woodcarvings while waiting for customers. This room became an art gallery where his creations were displayed and sometimes sold. Those who showed an interest in his work were invited into the gallery where Pierce would describe the meaning of each religious carving. As associate pastor at the Gay (Street) Tabernacle Baptist Church (now the Tabernacle Baptist Church), he often gave sermons that he illustrated with his woodcarvings and, at the end, he would present someone in the congregation with a small carving that he had made especially for them.

Pierce was content with his status as an artist within his own segregated community. However, the wider world was changing. In the 1960s and 1970s, the civil rights movement was breaking down cultural barriers, and many Americans were searching for a new kind of art, one that spoke directly to them about the American experience. Many collectors and trained artists saw that authenticity in folk art. In 1970, Boris Gruenwald, a Yugoslavian graduate art student from The Ohio State University (OSU) – which was near to the barbershop – met Pierce and saw his woodcarvings. Convinced that they deserved a wider audience, Gruenwald began bringing other OSU students and faculty members to see the work.

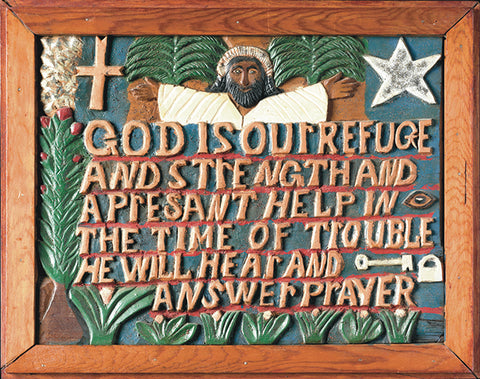

Untitled (God is Our Refuge), 1960, paint and glitter on wood, 18 x 14.5 in. / 45.5 x 37 cm, The Museum of Everything

Untitled (God is Our Refuge), 1960, paint and glitter on wood, 18 x 14.5 in. / 45.5 x 37 cm, The Museum of Everything

In 1971, Gruenwald arranged for Pierce’s art to be displayed at the university’s art gallery, then, in 1972, for it to be shown in New York City. He also entered the work into “Navi ’73”, an exhibition of the International Meeting of Naïve Art in Zagreb, Yugoslavia. That same year, Carolyn Jones Allport, a graduate student doing educational outreach at the Columbus Museum of Art, organised an exhibition of Pierce’s work. She had been introduced to the artist by Gruenwald. “On that first visit, I, too, fell under Mr Pierce’s spell,” she later wrote. To promote the exhibition, she enlisted the help of a local television station which broadcast a special programme about Pierce and his art. The exhibition was one of the most popular in the museum’s history. From that point, Pierce’s fame grew quickly, with numerous museums collecting and exhibiting his creations. Meanwhile, many of the collectors, students and artists who visited him during this time described him as a mentor and spiritual guide. He often told visitors, “Your life is a book... every day, you write a page”.

Pierce’s early years did not foretell a future as a renowned artist. He was born on March 5, 1892, on a plantation in Baldwyn, Mississippi, the second youngest child of Richard Pierce, a former slave, and Nellie Wallace Pierce, both devout Baptists. Pierce entered the world with a “veil” or membrane over his face which, according to local folk tradition, signified that the child would have psychic powers. His mother named him Elijah after the Old Testament prophet. When he was six or seven years old, his father gave him a pocket knife, and young Pierce began carving small animals and walking canes under the supervision of an uncle.

Pierce knew from a young age that he did not want to work on the plantation alongside his family; but, at that time and in that place, there were few options for a young, black man. As a teenager, he began working for a local barber, one of the few jobs open to him, as white barbers would not cut the hair of black people. It was also an occupation that suited Pierce as it gave him the freedom to take time off when he wanted to. He was a talented, sought-after baseball player and would often travel to African-American games in the surrounding communities. On one occasion, in about 1912, he went to play in Tupelo, Mississippi, and while there had a shocking and deeply affecting experience. That day – July 4 – a white man had been murdered and Pierce was mistaken for the killer. The sheriff intervened as a lynch mob gathered and, determining that Pierce was innocent, he released him and advised him to leave town quickly. Pierce did so, literally fleeing for his life. He would later depict that terrifying encounter in his carving Elijah Escapes the Mob.

This is an article extract; read the full article in Raw Vision #105