First published: Winter 2016

Call Justin. That’s what a municipal-government official in Denver, Colorado, instinctively did earlier this year when he learned that the representative of a local rescue organisation that aids people in crisis situations had come across some unusual pieces of “rubbish” that just might have had some value – as works of art.

Justin Massingale is an antiques dealer based near Denver, the capital of Colorado. Regarded as one of the best “pickers” in his area of seekers and discoverers of market-worthy cast-offs and collectibles, Massingale explores attics, old barns and estate sales in search of notable finds. When we met in Denver a few months ago, he recalled, “That city official knew that I’m always interested in seeing what people are throwing away, just in case there might be something of value. He knew I had experience with folk art and fine art.”

It turned out, Massingale explained, that the occupant of a small flat in Denver, an elderly man with debilitating illnesses, could not pay his rent and needed both housing and medical care. He had agreed to give his belongings to the rescue organisation in exchange for its assistance in moving him into a nursing home. Massingale said, “When I arrived at the apartment, he already had moved out, but I found a woman from the rescue organisation throwing his belongings out the window into a trash dumpster. She had come across some flat items, wrapped in tissue paper, that appeared to have had some value to the old man – otherwise, why would he have wrapped them so carefully? She also found some paintings.”

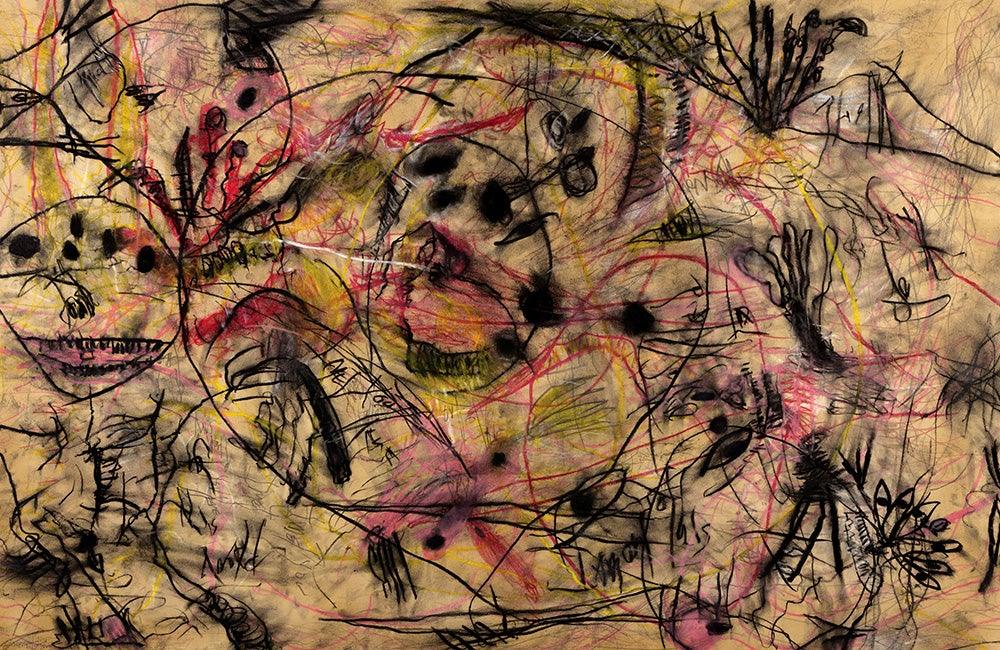

Untitled, graphite and pastel on paper

The rescue organisation was interested in any appliances or furniture that could be re-used. It was those items that the flat’s former occupant had agreed to give the group in exchange for its assistance. Rummaging around in the apartment, Massingale found piles of drawings of varying sizes; to his experienced eye, they appeared to have been made by the same person, along with various mixed-media objects he took to be sculptures. He also recognised that the paintings on canvas, some of which bore the modern artist George Tooker’s (1920–2011) signature, could have had both art-historical and market value.

“I didn’t know who had made the drawings, which were were full of intense, colourful images”, Massingale told me. “I just knew that I had to rescue all of the art from the rescue organisation, and my time was limited!” Soon, he met the creator of the unusual drawings and sculptural objects, an ailing man in his seventies. Born James Brown in North Carolina, he had legally changed his name to “Moshe Zephaniah Ezekiel Isaiah Mordecai Baronestrevenakowske”, or “Moshe” for short.

This is an article extract; read the full article in Raw Vision #92