First published: Fall 2008

Precious few artists are ever embraced by the mainstream art establishment. Fewer still achieve commercial and critical success. Even rarer are those who succeed despite working on their own terms, with little formal training and no gallery representation. When this last group does break through – the Dargers, the Wölflis, the van Goghs – recognition tends to be posthumous, if it comes at all.

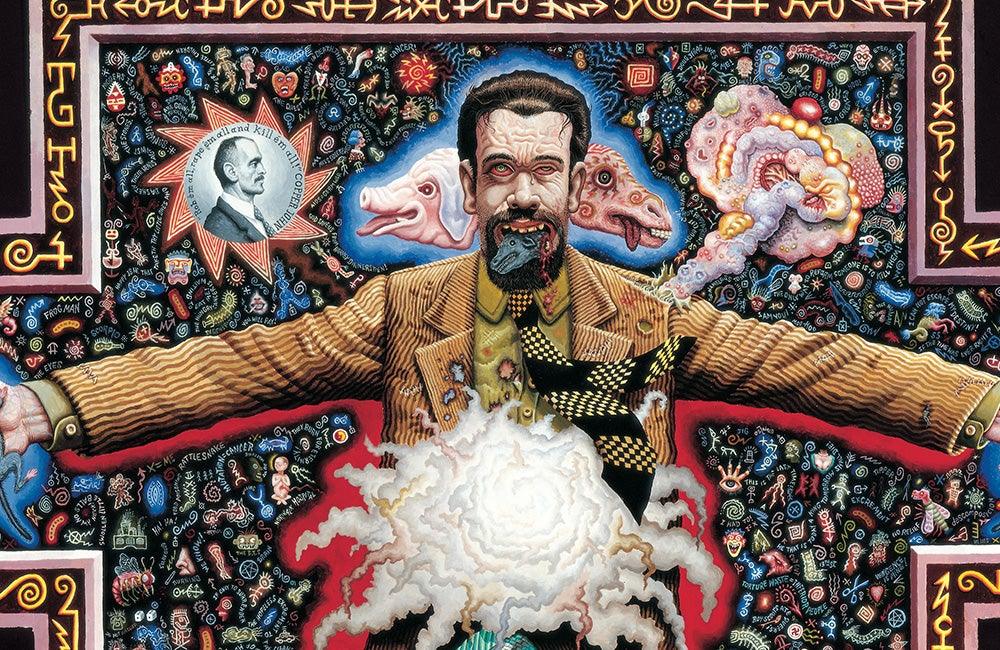

When such an artist’s subject-matter tends toward representations of murderers, serial killers, sideshow freaks, pustulent whores, apocalyptic catastrophes and visions of Hell, and chronicles society’s losers and outcasts – the lame, the infirm, the marginalised, the disenfranchised, the accused and the insane – obscurity seems all but guaranteed. Yet during the past year the international art establishment has recognised and validated a genuine renegade, a painter who has toiled for decades well outside its strictures: Joe Coleman.

It all began with a major retrospective: thirty-three paintings at an established, definitively uptown New York gallery (see Raw Vision 57), heralded with a full-page New York Times feature.

Curators from Paris’s Palais de Tokyo saw the New York exhibition and offered Coleman a one-man show in February 2007. In May, thirty paintings, as well as drawings, video and film, and objects from The Odditorium, Coleman’s private museum, were installed across all four floors of the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin. This past spring, recognition came full circle when over 20 of Coleman’s works were displayed in yet another gallery just off tony New York’s Fifth Avenue, together with works by Hans Memling and other masters of the 15th century Netherlands renaissance.

Museums in Japan and Italy have expressed an interest. It’s a now-or-never moment. Prior to the first New York show, almost no-one had the opportunity to see more than one painting at a time, as virtually all Coleman’s work is in private collections.

‘These are major exhibitions,’ confirms the artist, ‘not some rinky-dink space, an East Village gallery or outsider art thing. But I don’t want to use terms that could be taken as insulting. It means a lot to me that these places supported me early on. I’ll still always support places like that.’

This is an article extract; read the full article in Raw Vision #64