First published: Summer 2020

Bethlem artist Albert’s geometries of place and space

When a new inpatient joined the art group at River House in London’s Bethlem Royal psychiatric hospital, art coordinator Josip Livatovic and Bethlem Gallery founder, Karen Risby, were astonished to discover that he had brought with him more than 100 large drawings. Expertly executed in pencil and charcoal, he had made them during his previous confinements in prison and in Warlingham Park Hospital. It was 2007 when the new patient – known then and now only as “Albert” – revealed the drawings. Two years later, his work was chosen to be included in the “Outside In” exhibition at Pallant House Gallery in Sussex by then Head of Learning, Marc Steene. Today, Albert’s enigmatic drawings of architectural structures and geometrical spaces are displayed in Pallant House, the Bethlem Museum, the abcd Collection in Paris, and the Museum of Everything in London.

Albert is protective of his identity and his personal history, and Bethlem Gallery staff members have helped maintain his anonymity, understanding that medical histories and biographical details must not become the story and thus distract from the work itself. The artist is willing to divulge his year of birth (1962) and that he grew up in Thornton Heath, an unremarkable district of south London. One of his brothers was a talented poet, and Albert himself, as he puts it, “scribbled constantly” as a child. He simply describes his life after that as “difficult”. He is no longer hospitalised and lives in the community in supported accommodation, working at home, at the Bethlem Gallery or in a shared studio space.

Albert used to work on found paper and would carry his pictures around with him, cherishing them but not yet certain of their worth. Nowadays, he enjoys the fact that he has access to paper of adequate quality. He has a sketchbook to hand at all times and often works on three or four pieces at once, although he says that he subsequently rejects a quarter of all his drawings. He explains that the first transfer of the image from imagination to paper must be performed quickly so as not to lose it, but then perfecting the work can take days, even weeks. He has experimented with colour but mainly comes back to monochrome.

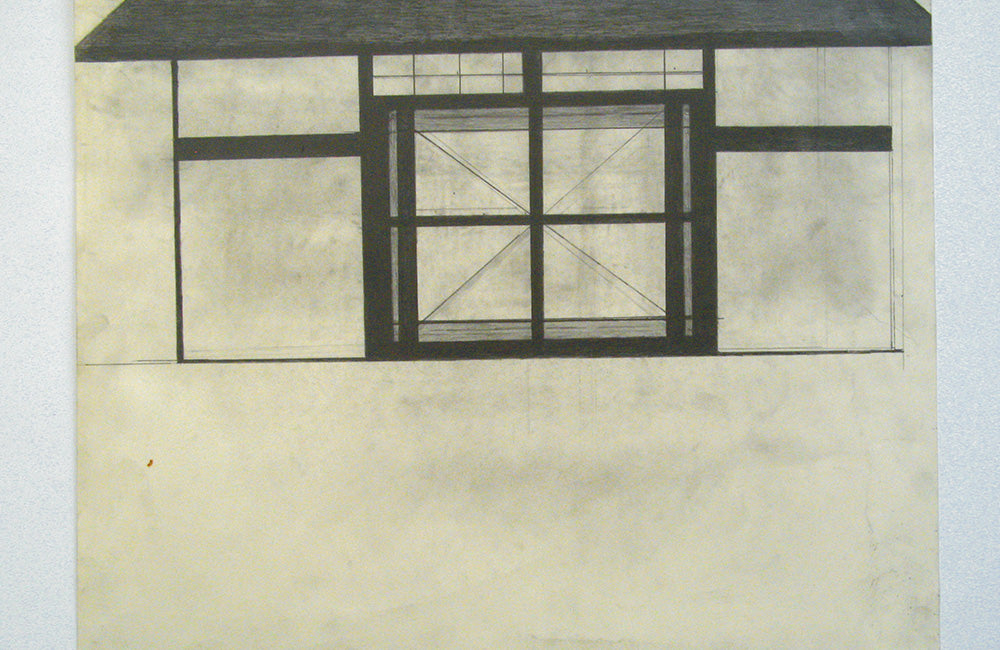

Untitled, 2012, pencil and pen on paper, 33 x 23 in. / 84 x 59 cm, courtesy: Bethlem Gallery

Untitled, 2012, pencil and pen on paper, 33 x 23 in. / 84 x 59 cm, courtesy: Bethlem Gallery

Could he see himself in another life as an architect? No, perhaps a doctor. Does his drawing mimic the work of a professional draughtsman? No, he measures himself against the great artists of British tradition – Turner and Constable, for instance – but feels he falls far short of their attainments. Albert’s comments can be self-effacing; sometimes, despite the international recognition he now enjoys, he argues even against the label of “artist”, saying that his work is more an all-consuming hobby, a function above all of time and effort. As former director of the Bethlem Gallery, Beth Elliott, explains, “Growing up in an underprivileged environment, Albert does not see himself as an artist... he has never had people around him who could have supported and nurtured that identity”. He deflects attempts by viewers of his work to discover profundity, to uncover mysteries. “Nothing magical,” he says, although it seems that he himself finds the processes of creation magically satisfying and mysterious. He answers questions carefully and firmly, politely resisting interpretations: no, the images are not about incarceration or containment, as some commentators have suggested, nor do they symbolise release from confinement. He says that if they represent anything, it is ideal places – places that he would like to live in and that he imagines others inhabiting. He adds that privacy and safety may be other elements that the designs evoke for him; the walls and fences are protective rather than restricting.

This is an article extract; read the full article in Raw Vision #106