First published: Winter 2018

The Smithsonian American Art Museum honours the life and work of Bill Traylor

Seventy years after his death and 40 years after his work came to the attention of a national audience, Bill Traylor’s (1853–1949) remarkable creative legacy is being celebrated with a major exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in Washington, DC. Traylor has come to be acknowledged as one of America’s most important artists, so this recognition seems long overdue. The landmark show encompasses 7,500 square feet on the museum’s first floor. For a man who spent his life in servitude and abject poverty, the exhibition goes a long way towards doing him posthumous justice.

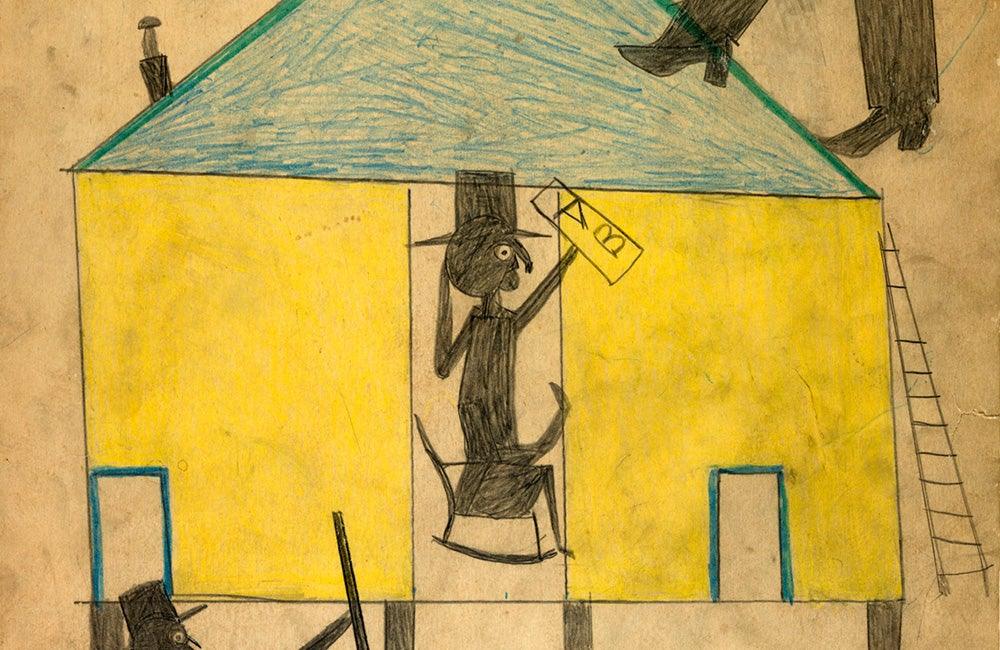

Untitled (Yellow and Blue House with Figures and Dog), 1939, coloured pencil on paperboard, courtesy of Smithsonian American Art Museum

Opened in the Autumn of 2018 and on view until March 17, 2019, it is accompanied by and critically fleshed-out in a 444-page monograph that shares the title Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor, published by SAAM in association with Princeton University Press. The book stands as a major contribution in its own right – essential reading for anyone who wants to understand American art in the twentieth century.

The project represents seven years of sustained effort on the part of Leslie Umberger, SAAM’s curator of folk and self-taught art. Except for an insightful introductory essay by contemporary artist Kerry James Marshall, Umberger is the sole author of the book, which breaks new ground in the scholarship on Traylor. In conjunction with the exhibition, Jeffrey Wolf’s informative and poetically evocative documentary film Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts premiered at the museum on September 30. A shorter, related film Wolf made serves as an introductory element in the exhibition.

The outlines of Traylor’s story should be familiar to anyone reasonably knowledgeable about twentieth-century American art, and especially to folk- and outsider-art audiences. And yet much of what we thought we knew of that story turns out to be wrong, or at least significantly incomplete. The exhibition and Umberger’s scrupulously researched book fill in many gaps while overturning some long-held assumptions, misinformation and misguided theories about the artist and his work.

Born into slavery in Alabama eight years before the American Civil War broke out, Traylor is known to have created more than 1000 works of art during the last decade of his life – images based on his memories, observations, daily experiences, and dreams. Most, if not all, of his surviving work dates from a crucial four-year period from 1939 to 1942. The exhibition’s 155 drawings have been carefully selected – not just for their visual strength or to reflect the range of themes he addressed – but, more importantly, for what they reveal about the artist’s life, his relationship to his place and time, and the ways in which his art changed and developed. All of these works are also included in Umberger’s book, along with a further 50 of his drawings that help shed further light on these particulars.

As an artist, Traylor was uniquely positioned in the overlap of multiple realities – cultural, social, and historical. The only known body of visual art by an American with first-hand experience of enslavement, his work offers a sometimes painfully revealing window into these overlapping worlds. A black man perpetually vulnerable in a viciously white-dominated society, he saw enormous historical changes locally and devised his own visual language for recording and commenting on them.

This is an article extract; read the full article in Raw Vision #100