First published: Spring 2013

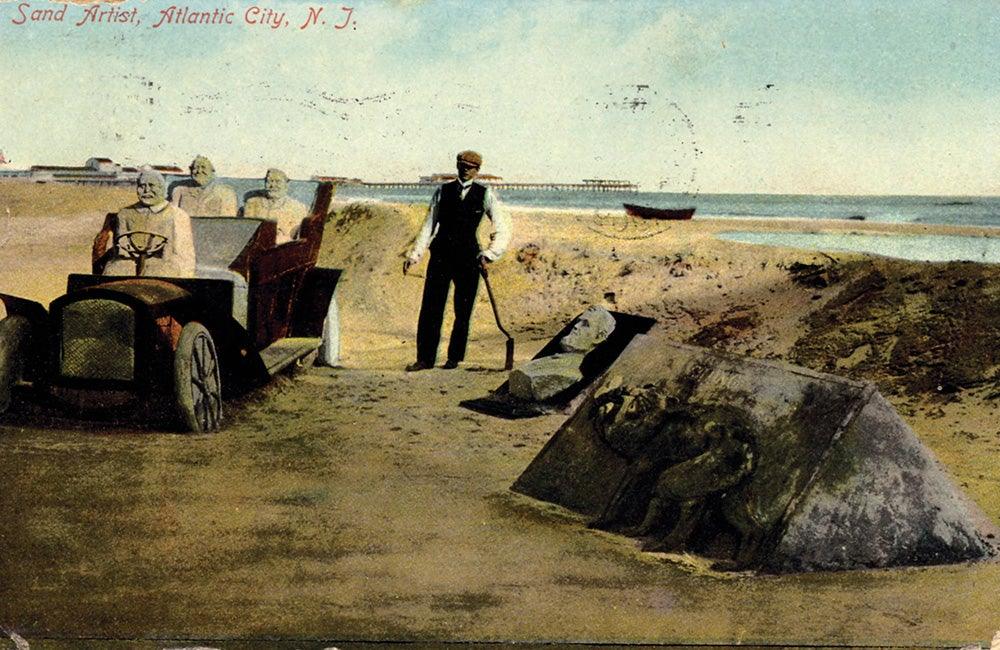

Sand sculpting is something of a sport today, attracting talented amateurs and enthusiastic families alike to contests across both North America and Western Europe. However, from the late 1890s until the mid-1940s men made a living from sand art, playing to beach and boardwalk crowds at burgeoning seaside resorts.

The growth of leisure time and summer vacations, along with improved and affordable transport, ensured a paying audience. The simultaneous birth of the picture postcard assured some immortality – if not for their actual works or their names, then for representations of their creations.

Yet, even in their heyday, these sculptors of summer, seen as superb showmen by some, were viewed as charlatans by others; con artists rather than sand artists.

Despite the down-market reputation of some sand artists, it was at the more refined resorts that American sand sculpture got both its start and staying power. Cedar Point in Sandusky, Ohio, was home to an unnamed master who, in the 1890s, recreated Rodin’s The Thinker along with a shipwreck, the Crucifixion and lions (which were to become a favourite sand subject).

The lion’s share of sand sculpture, however, was centred in New Jersey, particularly in Asbury Park and Atlantic City where swimming took second place to strolling. Not only did both attract the affluent, they brought conventions to their boardwalks which meant that hardier sand sculptors could work year-round. Conventioneers – particularly fraternal orders – and local businesses even commissioned them to create promotional sand pieces.

What helped in the off-season were sand pits constructed as protection from the weather – for the sculptors as well as the sculptures. These held as many as six men at a time. Another more controversial way of combating Mother Nature was to mix one part cement to three parts sand. This not only made sculptures longer lasting but sculpting faster, and was especially helpful with multi-panelled megastructures, often supported by wooden frames up to 20 feet long and at 45-degree slants.

This is an article extract; read the full article in Raw Vision #78