First published: Summer 2018

Edmund Monsiel was born on November 2, 1897, in Wożuczyn, eastern Poland. His father, Mikołaj, was born in Oszczów around 1865–66, and he worked as a carpenter on local estates in Wożuczyn. There, he settled and married Karolina of Dutkowscy, who was born on January 27, 1869. Together, they had nine children, but biographical records about Monsiel only mention two siblings, Aniela and Kazimierz. Mikołaj died in 1933 and was buried in Łaszczów. Tracing the family origins were not helped by there being three ways to spell the surname: “Monssiol” is engraved on Mikołaj’s gravestone; “Monsiol” was used by Mikołaj to sign Edmund’s birth certificate; and an error by the person preparing that birth certificate led to the name being recorded as “Monsiel”.

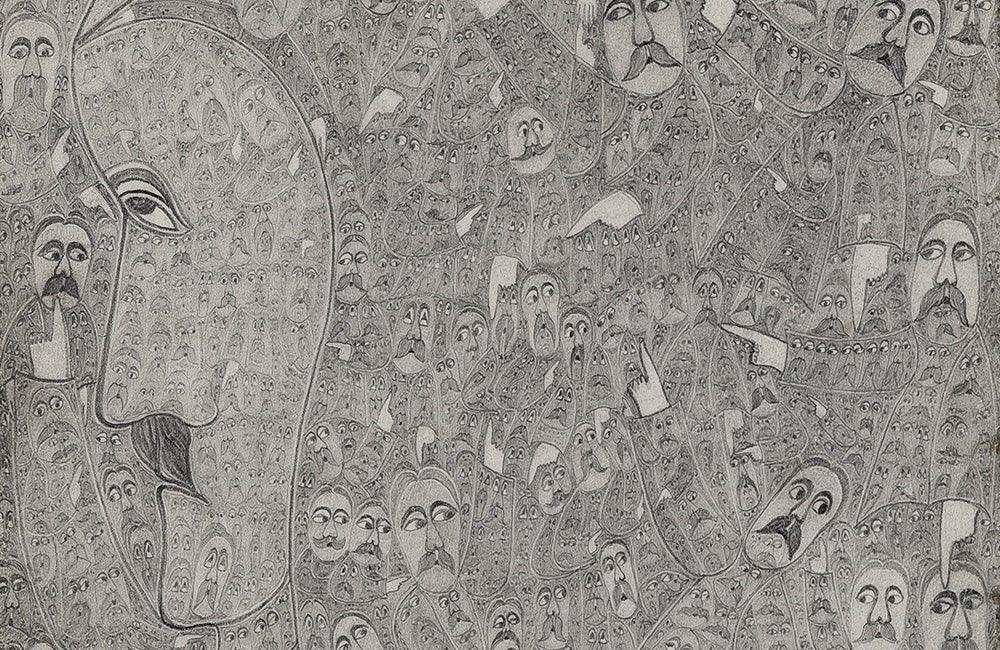

Monsiel family legend points to a French background. Following the French defeat against Russia in 1812, it has been said that a sick or wounded soldier from Napoleon’s army settled in Wożuczyn, in what is now the Lublin province. However, it is more probable that the family roots lie in a French craftsman who was brought to one of the local Polish courts. This is supported by the Monsiels’ reputation for being excellent carpenters – including Mikołaj. Monsiel accompanied his father to the local courts and churches in which he worked on repairs and renovations, learning the craft on the way. Young Monsiel was constantly exposed to local art, and one can see his observations of religious and secular art in photographs that he made.

Untitled, 1948, graphite on paper, 3.7 x 8.1 ins. / 9.5 x 20.7 cm, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Monsiel was educated up to a fourth grade level by a friend of Mikołaj, Władysław Chmielewski – a religious man and a patriot, who played the church organ. Monsiel then lived in Chełm before 1920 and attended the local teaching seminar for three years. In the early 1920s, he settled in Łaszczów, where he lived with his parents.

Monsiel and his parents lived at 3 Maja Street, where later there were three houses: one, with two living rooms and a shop, occupied by Edmund, and the remaining two occupied by his sister, Aniela, and her husband, Józef Wyrostkiewicz, who were raising Monsiel’s niece Jadwiga (whose father, Kazimierz, lived in Wożuczyn).

The shop was founded in 1923, selling stationery and other items, and Monsiel worked there until 1942 when it was supposedly commandeered by the occupying Nazis. However, Monsiel’s biographer, J. Olędzki, disputes this. It is possible that, like many businesses in World War II, it failed because of a shortage of goods.

A crucial event took place around Christmas, 1942. Nazis interrupted a church mass to select a group of people for execution – punishment and revenge for an armed assault on a station of German military police. Monsiel, his brother-in-law (Józef) and neice (Jadwiga) were in the church, and Józef was selected and murdered in a nearby forest. Many researchers have identified this deeply traumatic moment as the point at which Monsiel’s long-term mental illness was triggered.

About six months later, Monsiel moved to Kazimierz’s house in Wożuczyn. There, he hid in the attic. He would visit Łaszczów numerous times, going to the spot where his parents’ house had stood and his sister, Aniela, still lived. The family home was later burned down by the Ukrainians fighting with the Germans.

There is some controversy over the time that Monsiel lived in his brother’s attic. In Jan Mitarski and Ignacy Trybowski’s Świat samotnych wizji (pp. 3–7), the eminent psychiatrist Mitarski writes that Monsiel did not leave the attic for three years, despite requests by his family, and that he would come out at night but never left the building. Other researchers are more dramatic: Monsiel is said to have stayed in the small, unheated attic, with ceilings so low that an adult could not stand up fully. It was said that he spent his days there until the end of the war, talking to no one and gradually succumbing to paranoid thoughts while finding consolation in drawing. These descriptions do not fully correspond to the truth, as the attic was a habitable garret. During the war Monsiel rarely emerged, but this is understandable given the circumstances. After the war, he moved out and settled in an abandoned mill.

This is an article extract; read the full article in Raw Vision #98