First published: Winter 2018

Damian Le Bas Jr surveys the life and art of his father, a leader of the Roma Revolution

“Damian Le Bas is a tribe of one”, remarked the writer, critic and jazz singer George Melly in 1992. He had his reasons. Melly was opening a show of works by Le Bas at the Horsham Arts Centre, a glass-fronted theatre in one of the wealthiest corners of southern England. The invitation featured a drawing called The Council Tenants, in which wide-eyed faces stared from the windows of orange and purple terraced homes, and on display was a vivid portrait of Liz Taylor and Richard Burton, which Melly later acquired. The family of Le Bas’ wife (and my mother) Delaine, were in attendance, so the private view was full of Gypsies. Someone pointed at George Melly’s ring and shouted, “Dik at the fawni mush, it’s got a yawk in it!” (“Look at the ring man, it’s got an eye in it!”). Socialites and social housing; pastel drawings and plasterers; world travellers and Romany Travellers. It was a night emblematic of Le Bas’ artistic life.

It isn’t hard to see why Damian Le Bas (1963–2017) was often viewed – and viewed himself – as an outsider, nor why he hated any attempt to simplify, reduce or pigeonhole him or anyone else. Little about his life was straightforward. Le Bas was born in Sheffield in 1963, bearing an old Huguenot surname. Most of his mother’s family was Irish Catholic by descent, while his father’s side had connections to London as well as Derbyshire Romany ancestry. When he was ten, the family relocated to West Sussex, and by his teens he was an ardent supporter of three different football clubs: Sheffield United, Chelsea and Brighton. His friends would tease him about his split loyalties, but for him it was about staying true to his widely spread roots. In his art as in his conversation, he elevated the mixedness of the human condition to the status of the sacred, and the kaleidoscope of humanity remained central to his work until his death in December 2017.

After a turbulent time at school, Le Bas left early and fell in with some of the local scallywags and scoundrels in his adopted hometown of Worthing on the Channel shore. Many of his friends were older than him and he spent time on the streets, took drugs, got into scrapes and was forced to grow up fast. After a few years of life as, in his own words, “a little urchin”, an acquaintance’s sister spotted his drawings and suggested he apply to an art course to funnel his creative energy. He was accepted at Worthing Art College with no qualifications bar a small portfolio of drawings, before being set to work in an isolated shed, lest he distract other students with his music, jokes and inability to concentrate. He made friends with staff and students, but struggled to get his artwork taken seriously. One tutor suggested he’d be better off trying for a career as a stand-up comic. At one point, he produced a huge painting that provoked a Christian Union and local far-right British National Party protest. It featured the head of Moses and the words: “MOSES WENT UP THE MOUNTAIN AND WHEN HE CAME DOWN HE WAS A DREADLOCKS MAN.”

Le Bas struggled to fit into the Royal College of Art with the tutors. He seemed to care more about hijinks and DJing Northern Soul parties rather than studying. One tutor said his work looked like vomit, which hurt Le Bas deeply. For his final show, he exhibited all his possessions, every single one of which he had painted gold.

About this time he met Delaine and they married quickly, and, soon, I was born. People observed that Le Bas’ work was reminiscent of patterned fabric, so he applied to study textile design at the Royal College of Art, while Delaine applied to St Martin’s – against the odds, they both got in. Delaine’s Romany family and the big characters they mixed with – boxers, builders, horsemen, flower sellers, wheeler-dealers and pub-dwellers – fuelled Le Bas’ interest in his own roots, and repeated tattoo-like symbols began to appear in his work. Pound signs, paisleys, boxing gloves, horses and belt buckles cropped up alongside footballers, The Bible and the shamrock.

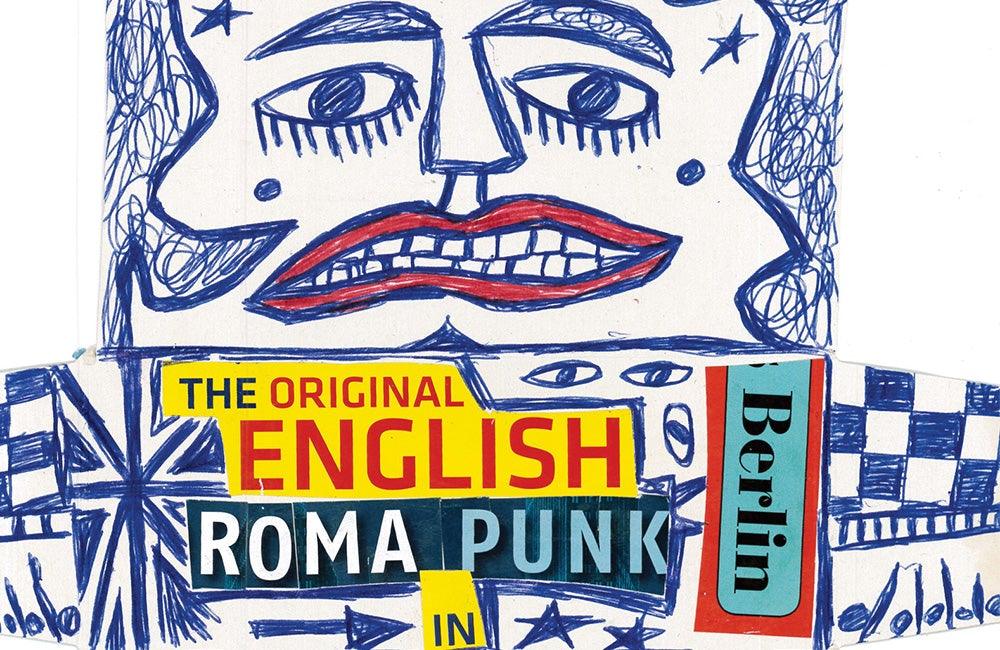

After graduating with a Masters degree in textile design, he focused instead on producing large, colourful drawings, centred on schematised human faces. A hallmark of his work from the late 1980s to the mid 1990s was the multicolour “forcefield” pattern of alternating bright lines that gave the images a hallucinogen-infused feel. While there was humour in many of his works, others were dark: The Death Car was created after his sister Marianne was badly scarred in a car accident and showed a naked, contorted woman on the roof of a moving car that had maniacal faces for wheels.

This is an article extract; read the full article in Raw Vision #100