First published: Summer 2019

An analysis of one of Willem Van Genk's most complex works

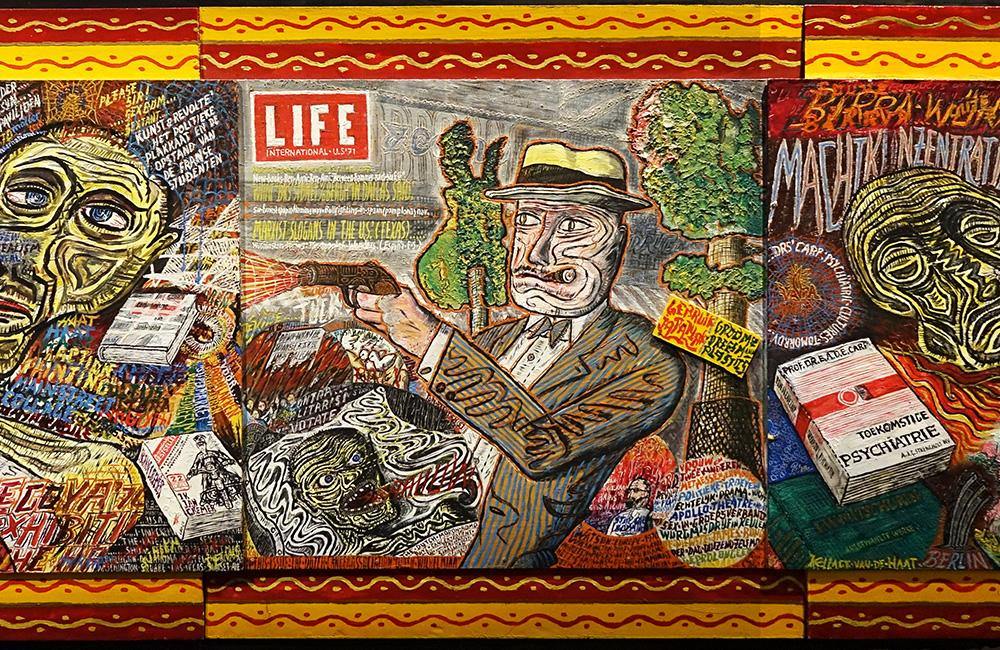

Dutch outsider artist Willem Van Genk (1927–2005) left behind a body of work that commemorates his life experience. His paintings and drawings are packed with layered, crowded and intricate detail – so much visual information that it can be challenging to untangle and interpret. His paintings can be seen as mind maps; complex networks of feelings and ideas. His 1971 painting Kollage van de Haat (Collage of Hate) is an important example of this and is analysed in detail in this article. To aid the identification of the areas of the painting that are discussed, there is an image key overleaf followed by corresponding numbered enlargements of details from the painting.

Kollage van de Haat (Collage of Hate), 1971, oil on board, 66 x 26 in. / 168.5 x 65.5 cm, courtesy: Collection of Willem van Genk Foundation

Kollage van de Haat (Collage of Hate), 1971, oil on board, 66 x 26 in. / 168.5 x 65.5 cm, courtesy: Collection of Willem van Genk Foundation

Van Genk grew up in The Hague, the only boy of ten children in a staunchly Catholic family. His sisters were at boarding school and, after his mother died prematurely from cancer when he was four, he was sent to stay with an aunt, his mother’s sister. From there, he went to two different boarding schools, but did not get on well at either. Once back at home, he tried to learn a profession and had a few jobs, but none lasted long. He would get distracted by his real interests, such as reading, trains and stations, and drawing. In the end, he was sent to Arbeid Voor Onvolwaardigen (AVO), an institution set up in The Hague to provide employment for people with disabilities. The name translates as “Labour for the Unworthy”, and to Van Genk it felt like a prison. After each day of meaningless work, he would go to his sister’s home to draw and paint – the only pastime that made him happy.

In 1958, aged 31, he presented some of his work to a local art academy. His large cityscapes in ink and watercolour impressed the assessors, but Van Genk’s psychiatrist at the AVO would not allow him to leave the institution to start an art course. To get around this, Van Genk started attending the academy in the evening to practise drawing, painting and engraving. Then, in 1964, the director of the academy arranged for him to have an exhibition, and so his career as an artist began.

In his drawings and paintings, Van Genk made many references to his life experiences, beliefs and values. He felt powerless as a person, and his art was a way to assert himself and to express his views and feelings. He was fascinated by the visible signs of power – uniforms, parades, weaponry, and military buildings and monuments. He wore raincoats, with ornate buttons, in a size that was too big for him to disguise his small frame and to give him a sense of being somebody.

Internally, Van Genk’s feelings of inferiority and insignificance persisted, but in the external world his career progressed until, by the 1980s, he had found his place as an established outsider artist. In the mid 1990s, he had a series of strokes and was hospitalised. While his health deteriorated, his status as an important Dutch outsider artist grew, and it continued to do so after his death in 2005.

Kollage van de Haat is a painful work to look at. It is a three-panelled piece, the left and right panels of which are each dominated by a large, deeply lined face. We can presume that they both represent the same person and that both are dead. In the left-hand panel, the eyes are open but the gaze is vacant and unfocussed. The figure is tightly wrapped up to the shoulders in a red blanket, while the folded-over top sheet is filled with elongated lettering inviting us to “Visit Union Tours for a trip to Asia”. The floral motif on the blanket resembles that of the ornamental borders that Van Genk’s father drew in his travel diaries. The words written across it “Cinderella hoesl” refer to a brand of bed linen. The figure has a label tied around his neck identifying him as “Wim van Gent” and implying that his empty stare is that of a corpse – the deceased is ready for transfer to the mortuary. A tiny Japanese cocktail flag has been pricked into his nose, which also bears the words “New Realism” and “New Deal”. The eyes seem dry, but their whites show the names of two Dutch rivers, the Vecht and the Rhijn, possibly alluding to streams of tears.

This is an article extract; read the full article in Raw Vision #102