First published: Winter 2018

How well can anyone know this artist and his work, and read the symbols of his faith?

Since the appearance of his work in “Black Folk Art of America, 1930–1980” at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC, in 1982, there has been much interest in Bill Traylor (1853–1949). Despite all the new information, books and exhibitions devoted to him, particularly in the last decade, mystery still surrounds certain aspects of the artist and his work. Most unanswered questions concern the level of his involvement with Conjure, the African-American religious practice, symbols from which seem to manifest in many of his drawings.

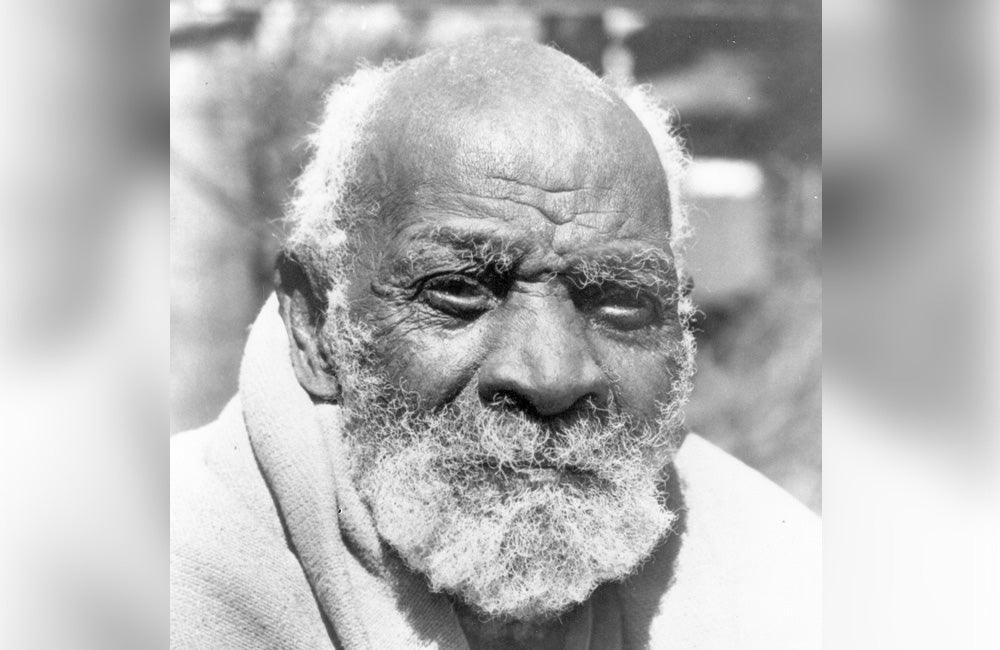

Probably the last portrait taken of Bill Traylor, c. 1948-49, photo by Horace Perry

From the beginning of African enslavement to the aftermath of emancipation and post-Civil War racial unrest, there was a widespread – although unofficial and little-researched – Creole religion in America. Sometimes called Conjure, it later became known as “hoodoo” in its desacralised and current form. In his book, Flash of the Spirit, Robert Farris Thompson called it “the old-time religion”.

The practice of this religion was an enslaved people’s spiritual survival strategy, using cultural resistance to create and find a common ground under the most oppressed and destabilising circumstances. It was not dogmatic, it was fluid, and it was the worldview that black Southerners grew up with, more orthodox early on and more grassroots in the present. This was the world in which Traylor grew up.

The discourse around Traylor’s life exposes both strengths and weaknesses in the methodology of presenting the work of an important artist who was never professionally interviewed or researched in his lifetime. The two most powerful areas of his biography are the context of his cultural immersion and the drawings themselves. They make for a dangerous territory. Some say intentionality can never be deduced, and some say that when the work is fed from the sources of the culture, as Traylor’s certainly was, and enough common factors emerge, a cultural intention can be found.

There is a flaw in the word “intentionality” in that it conflates two very different concepts: what the artist “intends” the specific work to say, and how and why the art is made. We can also include the question, “For whom is the work being made?” When the mainstream uses the word “intentionality”, it usually refers to what the artist intended the work to mean. This is not usually seen as a necessarily good thing. The mainstream wants to deal with the art purely formally, and this often strips it of any meaning at all.

We are left with several choices of path. One, widely held in the more commercial infrastructure of the field, is that Traylor’s work is more or less what it appears to be – that what you see is what you get. Granted, this is a rather outmoded viewpoint that can be summed up in the following statement by one of its proponents: “Sometimes a horse is just a horse”. Those who follow this line seem to ignore the underlying violent, ambiguous or culturally specific tones in some of the drawings.

The second viewpoint is that, though till now left unproven and uninterpreted, some of the drawings give evidence that Traylor himself was either a Conjure man himself or was portraying Conjure in his works.

The third, and strongest, viewpoint is that the drawings were produced from the perspective of someone living within the Conjure culture; that there are enough images evident in the Conjure language, but thus far there is no actual proof that Bill Traylor was a Conjure man – yet many of the drawings seem to be in a Conjure context.

This is an article extract; read the full article in Raw Vision #100