First published: Summer 2014

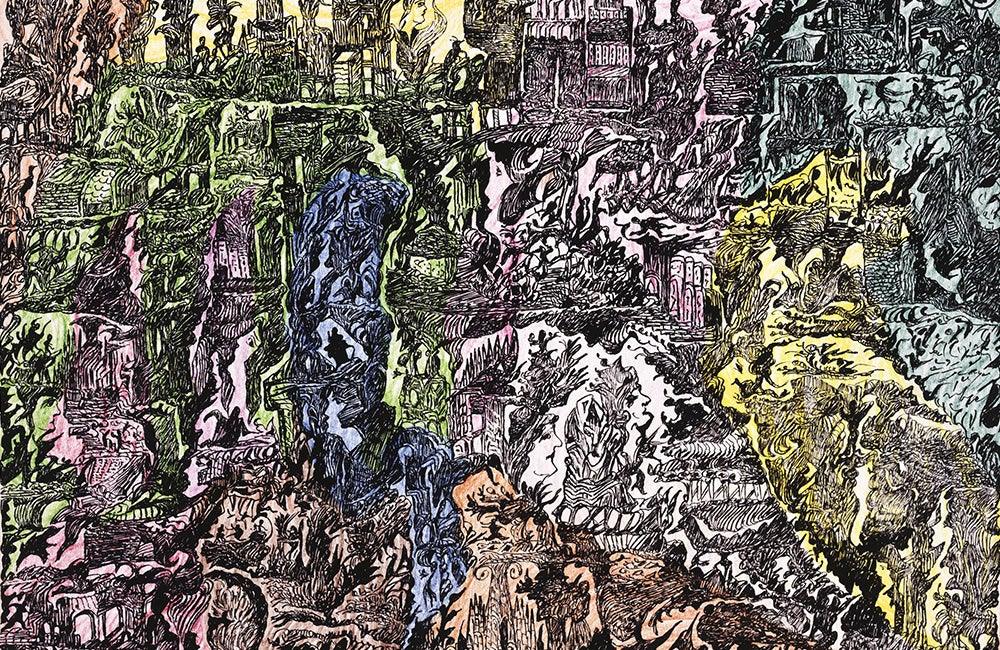

Marginal drawings, in manuscripts both ancient and modern, have a mysterious attraction, all the more because we can only guess at what might have prompted them. Often, especially with scribes, there must have been an element of kicking over the traces, a sort of graphic truancy, sometimes even a revenge of the image over the alphabetic system and the institutional authority behind it, that penned it in. This flavour of insubordination carries over into the modern phenomenon of doodling, a term that suddenly gained currency in the period between the wars and spawned a number of doodle “dictionaries.” The interpretations they offered were influenced by a mix of graphological and psychoanalytical concepts, almost as if the external rebellion of earlier times had been superseded by an internal, unconscious one.

As Russell Arundel, author of Everybody’s Pixillated (1937), put it, "While doodles appear to be aimless pixillations they are in reality accurate pictures of the Subconscious Mind. They are psychic blueprints of man’s inner thoughts and emotions that have slipped from the deeps of memory onto paper."

Three Women with Baby, Madge Gill, c. 1947, ink on paper, 19 x 25 ins., 48.3 x 63.5 cm, courtesy London Borough Newham Heritage and Archives

Three Women with Baby, Madge Gill, c. 1947, ink on paper, 19 x 25 ins., 48.3 x 63.5 cm, courtesy London Borough Newham Heritage and Archives

Whilst many of the published doodle interpretations use material solicited from celebrities, and give suitably flattering readings, there are some from more popular sources, most notably the results of a competition run by a London newspaper in 1937, for which over 9,000 doodles were submitted. Coincidentally, three psychiatrists from the Maudsley Hospital wrote up a very general analysis of them, seeing them as evidence for a lowering of consciousness and a descent to a more “primitive” level of mental functioning.

In their classic form, doodles have a casual and democratic character: they are made absent-mindedly, often by people with little or no artistic pretension, and they have a surreptitious and disobedient flavour to them. This already has something in common with outsider art. In fact, in the course of shaping his concept of Art Brut, Dubuffet also expressed an interest in such spontaneous and rudimentary mark-making, and proposed, “To feed off inscriptions, instinctive markings. To respect the human hand’s impulses, its ancestral spontaneities when it traces out signs.

This is an article extract; read the full article in Raw Vision #82